On March 8th I boarded a plane that took me from Houston, Texas to South America. My destination? Cordón Caulle: an active volcano in the south central Andes. My task? To take measurements of residual heat and gases from the most recent eruption and to record the ever evolving landscape [Story link- How hot is hot?], all while enduring 4 AM wakeups (for research), unfettered elements, and ubiquitous dust on the flank of this slumbering behemoth. You might wonder why on earth someone would choose to do this (yes, I did so of my own free will). I then answer with a question of my own: why wouldn’t you?

I know and appreciate all the reasons NOT to go. One of my fellow graduate students was offered the chance to go with me. I told him we would be tent camping for two weeks without showers or even a bathroom. His answer was a simple, “No thanks.” I suspect he represents a majority, while I, along with my four fellow expeditioners, are a very small minority. But that’s why this blog exists! So all of you whose knee-jerk reaction to this scenario is “no thanks,” can yet experience what it’s like to live on a volcano for two weeks, all from the comfort of your couch. And for a few of you reading this, I hope I can inspire you to choose the experience of a lifetime over the minor inconvenience of no showers.

So why did I purposefully embark an expedition to a dangerous, inhospitable volcano in the middle of the Andes? Was it the danger, the chance to face nature in its rawest form? Was it the challenge of going to a place so difficult to access that only a handful of people have ever trekked? Not entirely. I suspect everyone who went would agree these reasons only enhanced our anticipation for the adventure, yet none of these were the primary reason.

Ultimately, we are volcanologists—people who study volcanos for a living—and we had questions that could only be answered by the volcano itself; data that was only available on the volcano. Observations and samples that needed to be collected to paint a real-time picture of what was going on under our feet today to better prepare those living in its shadow, of what might happen tomorrow. [Story link- Chasing the heat: My story]

We could have chosen one of hundreds of previous eruptions to study and never left U.S. soil. Many American volcanos don’t even require camping to study. We could have stayed in a cozy cabin and drove to our field sites had we stayed in America. Instead, we needed a helicopter to transport us and our supplies to our campsite. That’s right, we had a helicopter [Story link- Hot drop offs]! Unfortunately, we couldn’t use the helicopter to go out for dinner. Instead, we got creative with how we cooked our chicken [Story link- Hot rocks = hot chicken]. Rain or shine, ash or snow, our only protection were individual tents and a little makeshift group shelter cobbled together with a tarp, some paracord, rocks, and sticks (Volcano Research Helpful Hint #1: always have a good knife out in the middle of nowhere) [Story link- Cooling down at camp].

So if we can study similar volcanos in relative luxury and safety close to home, why did we choose to go to Cordón Caulle? Because while other volcanos may be similar, none of those can provide the specific, near real-time knowledge about large, explosive, rhyolitic eruptions that we would find at Cordón Caulle (Geology term #1: rhyolite is a type of extremely viscous lava—think molasses in Antarctica and you still won’t be viscous enough—made up of greater than 70% silica (SiO2). Rhyolitic volcanos historically produce some of the most dangerous eruptions, hence we study them.). [Story link- How hot is hot?]. We haven’t experienced an eruption like this in living memory, yet we have evidence of them occurring in places like California as little as 1000 years ago. Erupted 2011-12, the hardened lava flows, layers of ash, and residual heat of Cordón Caulle provide us the perfect opportunity to explore a living, breathing volcano capable of producing some of the most dangerous eruptions on Earth.

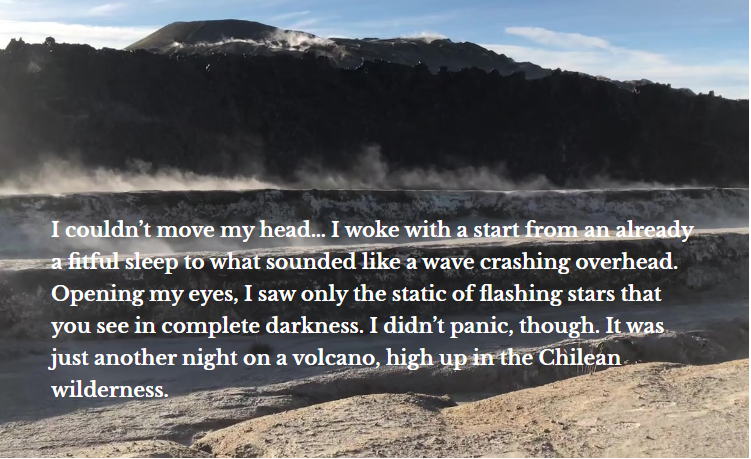

For two weeks, I lived with a volcano. My energy came from the residual heat rising from below to my feet, and giving rise to the steam that I was bathed in and breathed every day. The ashy blanket we camped and traversed on may have separated me from boiling water below, yet always with the concern that my feet might collapse through the fragile crust, bringing to bear the full force of the volcano’s heat. Around every turn a new sight filled my eyes with otherworldly cracks and crevices, some extending down to what seemed like the bowels of the Earth, emitting noxious gases that had to be measured without falling in. Ways across these menacing vents had to carefully navigated, knowing that help was likely too far away for comfort, to see what secrets we could discover over the next ridge.

In some areas of the lava field, there is no way to traverse in or out. Standing on the hardened surface of still steaming lava, I realized my colleague Heather and I were the first and only people on the planet who had ever stood in that spot, because a helicopter had to place us there [Story link- Hot drop offs].

Each day I was reminded how fortunate I was to be counted among the few people who have explored this volcano. Every night I went to sleep not knowing if the slumbering beast would awaken, but I couldn’t let that bother me for want of a good night’s rest. Many people spend their entire lives within the shadow of an active volcano never considering the hazard. So after our field work was complete, we went to the little town of Neltume to speak to school children to teach them about their local volcano [Story link- Sharing the ember: Outreach].

Closing my eyes the night after the abrupt and confining start of my day, I ponder the 4:30 AM alarm and the next day’s physically demanding tasks. I settle down into sleep, content with appreciation of the unique opportunity I have been given to spend the night on the flank of an active volcano in Chile.

All of Patrick's research blogs can be found here: https://patrickphelps.org/