Ramiro[1] lives in the Colombian highlands. Every day he gets up to work in his sugar cane and coffee crops located on the banks of the Magdalena River, very close to its source. This river, one of the most important watercourses in Colombia, rises in the highest part of the mountains, where vegetation, soil, and climate converge to capture and store water. On its way to the Caribbean Sea, the river crosses the country and structures a large part of the territorial and economic organization of the western part of the country. Today, along its banks, large agro-industrial crops are grown, and its water is used in twenty-four dams that supply energy to this part of Colombia. In addition, this river basin is home to peasant and fisherfolk populations that have found their living spaces on its banks, such as Ramiro's family, who have lived near the source of this river for several decades.

One day about eight years ago, Ramiro went to work on his farm. While preparing the land for cultivation, he came across a large, heavy cement block with a metal plate embedded in it. On the plaque were some acronyms, numbers, and a date. Intrigued, Ramiro began to ask his neighbors about this strange marker on the ground. Sometime later, he and his neighbors realized that these markers in the land were present on several of their properties, but they had no more information about it. What did the metal inscriptions mean? Should they be worried?

Shortly after that, other markers began to appear in the villages. This time on the trees, the villagers found metal plaques that read: "Parque Natural Regional Corredor Biológico Los Guacharos-Puracé" (Los Guacharos-Puracé Biological Corridor Regional Natural Park). By then, it was clear that this was a new protected area, in addition to the Purace National Natural Park that had existed in the area since the 1970s to protect the highest part of the source of the Magdalena River. This National Park had not been of concern to the village's inhabitants because its area did not include peasant farms. However, this new protected area did seem to cover the areas these families currently inhabit.

The lack of information about this new protected area caused fear and uncertainty among Ramiro and his neighbors. This area was declared in 2007 by the regional environmental authority to extend the protection of the river's source, limiting the development of agricultural activities. The markers were installed shortly after that, but apparently, the community was not informed. For this reason, when the locals found the cement blocks on their land a few years later, there were more questions than answers among them. What are the implications of this declaration? Where is the limit of the new area drawn? How would this declaration affect property rights and land values? What would happen to their crops, their houses, and their animals? Would they be able to continue living on their farms?

Thanks to the Expanding Horizons Fellowship, I visited Ramiro and some of his neighbors in the summer of 2022. They told me the story of the markers found on their land and how they have lived during these eight years, uncertain about the consequences and implications of this protected area. They say they have not received precise information about the area's declaration process or limits. In addition, the inhabitants have other concerns about their territory and the possibility of staying on it.

On the one hand, approximately 12 years ago, Colombian environmental authorities, private consulting companies, and international cooperation agencies began formulating a project to implement REDD+ mechanisms, including the sale of carbon credits in this protected area. Participation in this project involves signing agreements, some of which include giving up farming on their land in exchange for receiving monetary benefits. Although the institutions claim to have been widely informed about this project, the inhabitants of these villages claim that they do not have accurate information about the implications of joining this project, nor about the benefits or risks of receiving project support to stop cultivating and dedicate their land to conservation. Moreover, in recent years, there has been a significant increase in the purchase of large tracts of peasant land by the Enel-Emgesa power generation company. This company built a hydroelectric plant inaugurated in 2011 downstream from where Ramiro and his neighbors live. These land purchases coincide with the areas declared as protected zones. The company intends to allocate these lands to the conservation of the upper part of the basin and thus ensure the proper functioning of the dam. For this reason, given the uncertainty of the future of agricultural production in this area, some residents have decided to sell this land and migrate elsewhere.

The concern of the inhabitants who refuse to sell the land and to participate in the carbon market project is for the future of the territory and their families, who have lived there for so long. What will happen in the coming years if they cannot produce food and if the purchase of land advances to the point of depopulating the villages? What can be done to guarantee a future life in the Colombian high mountains that does not exclude their presence and livelihoods but also allows the care of the water of the Magdalena River?

With the support of the NGO ForumCiv and the EAN University, Ramiro and neighbors from nine other villages have set out to address these concerns and uncertainties for the future of the peasant territory. Since 2019 they have been working on formulating a proposal for environmental authorities that includes alternatives to developing strict conservation policies in peasant territories. As a result, they have resorted to a Colombian agrarian public policy mechanism called Zona de Reserva Campesina (ZRC) (Peasant Reserve Zone). This mechanism opens up the possibility of reconciling production and conservation through the design of local development plans aimed at improving the quality of life of peasants and, at the same time, promoting nature conservation processes. However, the constitution of these zones requires a lengthy administrative process, which includes drafting documents identifying the territory's characteristics, the inhabitants' needs, and the environmental conservation challenges.

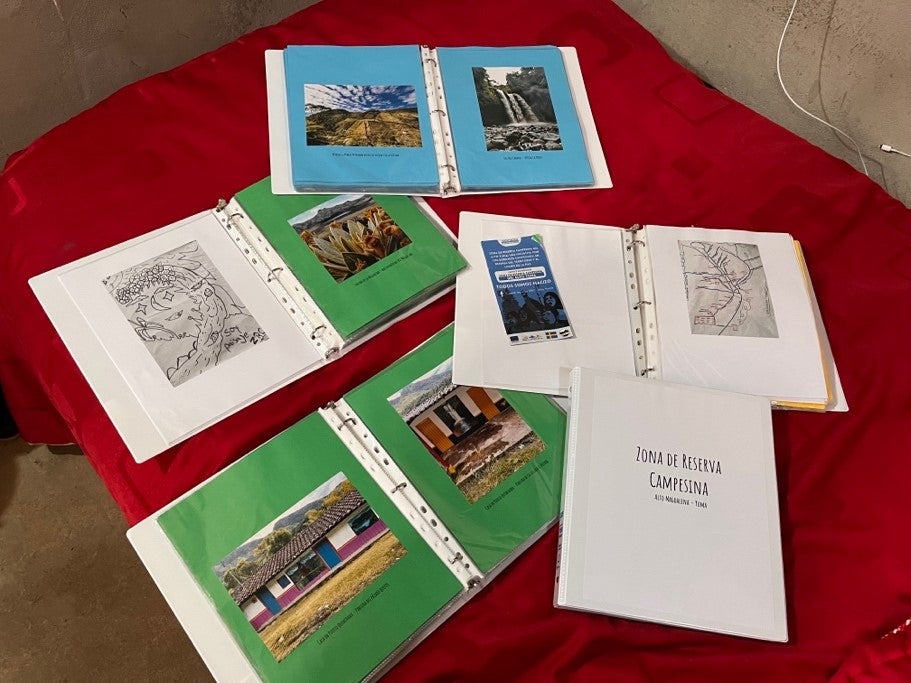

My trip to Colombia allowed me to collaborate with the process of formulating these documents. During this time, I visited the families in these zones and accompanied them to tour the farms, looking for the markers that were supposed to indicate the limits of the new protected area. I also attended some of the leaders in several meetings to explain the ZRC public policy mechanism and helped them explain its constitution's administrative process. During these visits, the leaders gathered geographic information on the location of the points using GPS. In addition, we took photographs of the areas they plan to include in the constitution of the ZRC.

As a result of my visits, I helped organize the cartographic information collected during the field visits. In addition, I reviewed the documents, administrative acts, and geographic data related to the declaration of the protected area. By gathering the information in specialized software and contrasting it with the official documents, the peasant leaders and I could identify inconsistencies in the protected area's limits and the markers found by the farmers on their properties. We also realized that these limits and the regulations of the protected area had changed three times since it was declared in 2007, changes that have yet to be socialized to the territory's inhabitants. Although the reason for the changes is not yet clear, our analysis shows that in the areas closest to the source of the river the restrictions have become stricter. The conclusions of this analysis were consigned in a document delivered to the leaders of the peasant organization. This document includes maps and recommendations to move forward with establishing the ZRC.

Additionally, together with the peasant leaders, we developed a photographic project that brings together the images taken during the tours, the photos they had in their archives, and the social cartography exercises they had advanced to date. The objective of this process was to create a photo album of the places where the farmers live, highlighting their relationship with water and the livelihoods they develop on the banks of the Magdalena River. This album will accompany the technical documents used for constituting the ZRC, to make the territory's problems visible. We organized seventy photographs in folders and distributed them in the territory's villages. We also created a virtual album that was shared via Twitter and Facebook.

The advances in drafting the document and creating the photographic album of the territory are contributions that my visit allowed in the long road of facing the complex challenges of reconciling agricultural production and water conservation in this territory. In addition, sharing with the inhabitants of this village allowed me to advance in the design of my doctoral research project. My dissertation aims to understand science's role in public policies related to biodiversity conservation in Colombia, which have focuses mainly on prohibiting productive activities such as agriculture and livestock. I aim to analyze how some technical and scientific practices contribute to understanding agriculture and conservation as different and opposite practices. Therefore, meeting Ramiro and his neighbors and collaborating with them was significant in defining my project's objectives and scope. Also, it helped me glimpse my research's contributions to addressing the dilemmas of conservation and care of water and biodiversity in Colombia.

[1] Ramiro's name was changed to ensure his anonymity.